The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.”

- David Harvey, The Right to the City

Modernist heritage and revaluation

A central premise of the biennial is that modernist heritage cannot be separated from the grown social fabric of neighborhoods. In both Arnhem and Nijmegen, architecture from the 1950s and 1960s is considered iconic. Modernism reigned supreme in these years and had its influence on the way in which the reconstruction districts were inhabited and made habitable after World War II. The social fabric there is still influenced by these developments to this day. The biennial can therefore be seen as a plea for the revaluation of modernist reconstruction neighborhoods.

The reconstruction era, foundation for a microcosm

In addition to the city centers of the reconstrucion era, the program of the biennial unfolds in the neighborhoods of Hatert/Dukenburg in Nijmegen and Presikhaaf in Arnhem, largely built between 1945 and 1965. In the year 2022, these are cosmopolitan neighborhoods, where the whole world comes together. Presikhaaf is now home to 16,000 people born in 120 different countries, creating a special dynamic. Hatert, with 10,210 residents and dozens of different nationalities, although not identical, presents a similar picture. In the reconstruction neighborhoods - as in many such neighborhoods elsewhere - a special microcosm of cultural exchange has emerged, with its own notions of engaged citizenship and a specific social cohesion.

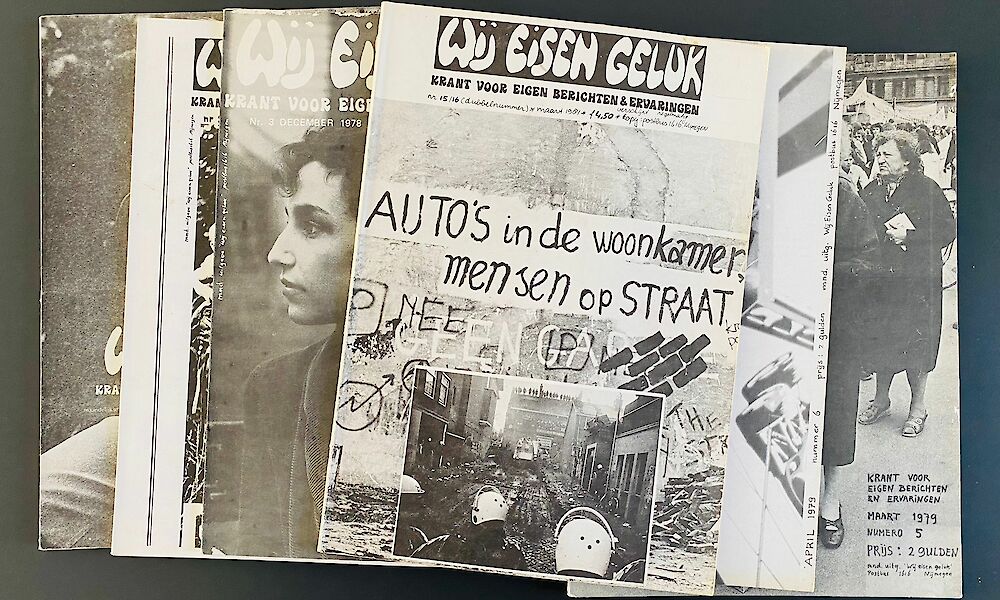

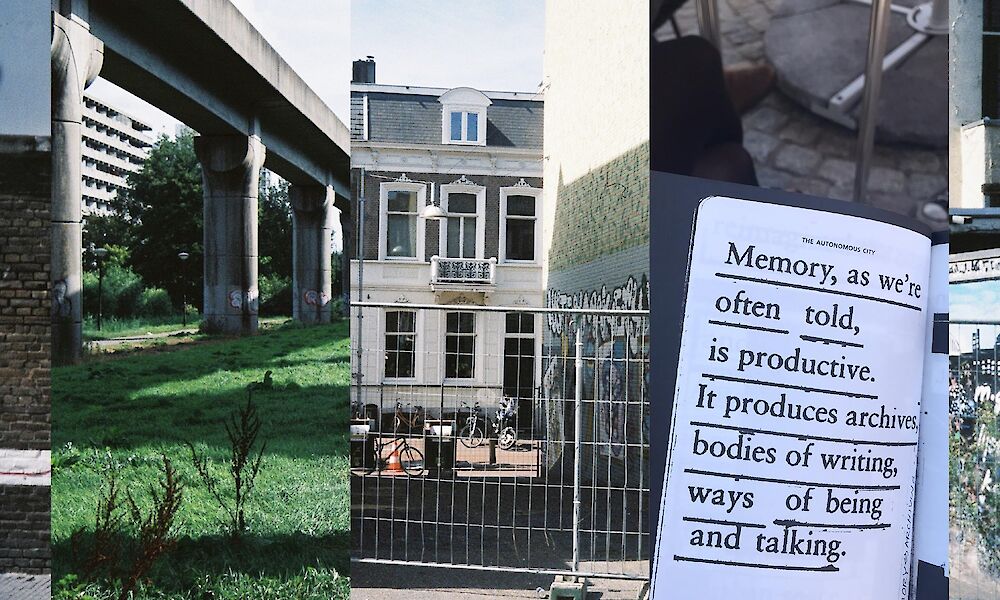

Forgotten histories and influence

Together with creators and communities from Nijmegen and Arnhem, P1 uncovers forgotten communal histories that cause friction with the dominant narratives of postwar modernism. At the same time, we respond to current processes of gentrification, demolition and urban restructuring, within which existing communities often have too little say. Residents are sometimes allowed to have a say, but hardly ever have actual influence on their own living environment. P1 uses the biennial as a vehicle to connect to ongoing processes of urban development in Arnhem and Nijmegen (or rather, it stems from them). P1 reverses the top-down modernist design paradigm (the notion of a manufacturable society) and proposes a design process in which the urgencies articulated by already rooted communities are taken seriously and made visible. In the Biennale Gelderland, this is expressed in part through the intensive involvement of junior curators who continue an earlier investigation into who defines what heritage is. Also, P1 makes careful choices to collaborate with artists who are connected to the region through their work or background.

P1 feels a kindred spirit to Sonsbeek 20→24 and the 12th Berlin Biennale, however with a more radical stance: P1 makes the knowledge of local communities the starting point of its programming.

The Future

P1´s digital platform and the prospect of a permanent base of operations in Arnhem Presikhaaf offer the opportunity to continuously place important themes on a public agenda. Podcasts and liveradio, research and interviews, poetic reflections, documentation of artistic interventions will be gathered on the digital platform that forms a foundation, a kind of 'hub' of global knowledge exchange, for short- and long-term activities. The digital platform is developed with a sensitivity for the hyperlocal and hyperinternational character of our growing network of comrades, consisting of residents, researchers, architects, urban planners and artists.

Text: Claudia Schouten